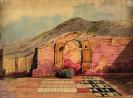

The main water sanctuary in the Châtillonnais region is the Cave at Essarois. It was excavated in the 19th century under the direction of Victorine de Chasteney, a woman of letters and the site's owner. Abandoned during the Gallic Wars, the site was rebuilt about a decade later using Roman construction techniques. The temple was then dedicated to Apollo, the healing god.

Pilgrims came to seek healing, offering statues representing their ailments, or giving thanks to the deity—as evidenced by hands bearing fruit. These figures span all ages and reflect the social hierarchy: a man in a rich Roman toga, simple, rough-hewn faces for the poorer classes, pregnant women, children, the young and the elderly—all express the pain of illness or the relief of recovery. In the end, this statuary reflects the full breadth of the human condition.